Planning and Organizing

The importance of thorough and careful planning and organizing of a digital archive at the very beginning of the process cannot be overestimated. A well-devised plan for the archive will provide the grounds and guidance for decisions and actions throughout the digital archiving process. On the flip side, a poorly considered decision or an omission in this phase will create additional difficulties in further phases and actions in a digital archive’s life cycle.

The key activities at this stage include devising a General Plan for the digital archive, creating an inventory and selecting the material for preservation, organizing and describing the material to devise a structure for the future archive, and planning the Digital Archiving System and selecting its main hardware and software components.

General Plan

Creating the General Plan is a crucial first step in the process of developing a digital archive. It lays out the reasons for and the method of the archive’s development by providing it with Guiding Principles as well as key decisions regarding the content, access, and major organizational, technological, and resource-related issues. Such widely scoped, detailed, and advanced planning will help the organization navigate a wide array of challenges that will need to be met in the later stages of the process of digital archive creation.

It is important to note that the General Plan should record not only the conclusions and decisions but also the reasoning and grounds on which they are made, as doing so assists their later review and potential revision, especially when context or circumstances change.

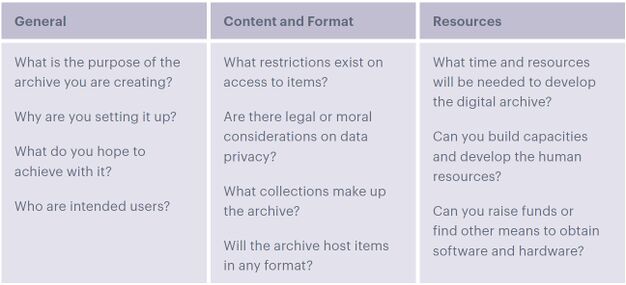

There is no universal template for a General Plan for digital archiving, and this document’s usefulness will differ somewhat depending on the content and context of the collection and the organization itself. However, there is a set of questions that can be a useful guide for the development of a General Plan. These questions concern the content and purpose of the future archive, as well as organizational, technological, and resource-related issues. Detailed, well-informed, and considered responses to this set of questions will give you a solid basis for devising a General Plan.

Figure 2 provides an example of a list of questions to be answered in developing a General Plan for a digital archive. Just so you know, this is just an example of a list, not a template, and as such, it can be amended and tailored to the needs of a particular archive and organization.

The responses to these questions can be divided into different segments of the General Plan. These will serve as the Guiding Principles for developing the digital archive.

Guiding Principles

The Guiding Principles summarize the reasoning behind the development of a digital archive. They state why an archive is needed, who will be using it, how, and the expected benefits of its creation and development. The Guiding Principles also address key issues, including the required resources and technologies, legal and security-related responsibilities, and organizational matters.

The Guiding Principles should serve as a reference point, a measuring stick for any future major decision or action to be taken in the process. For example, suppose one of the benefits of the digital archive is maintaining the credibility of data and recording the chain of custody over a digital object. In that case, we can rule out any software or system solution that does not perform well on that function. Similarly, we will not implement any data security solutions that would obstruct access for a key group of users.

Although foundational for a digital archive, the Guiding Principles are not “set in stone” and can and should be reviewed and amended when necessary. Over time, with changes in the archive’s external community, technological development, and the iterative transformation of the archive itself, the organization might decide to alter the archive’s Guiding Principles to suit the changed environment better.

A fictional example of a General Plan is provided as an addendum at the end of the manual. In that example, we include a set of Guiding Principles that should be included in any digital archive’s planning and development. It also briefly describes the main considerations and issues to be addressed by each Guiding Principle and how these can be formulated. This example should not be considered a definitive list of Guiding Principles nor used as a template.

Identification, Selection, and Prioritization

Simultaneously with developing the General Plan, we must identify, evaluate, organize, and describe the material we wish to preserve. This will allow us to map the material and gather and arrange key information on its characteristics, which creates the basis for further archival processing. It is also a necessary step to enable us to make any planning and decision-making on how the material can be archived and preserved and how the Digital Archiving System can be built.

Handling Unstructured Physical Archival Material

At this point, many CSOs following this manual in developing their digital archive will find themselves faced with the challenge of handling numerous, unorganized batches of their physical material—be it boxes full of mixed-up files, shelves with random folders and documents, or boxes full of unmarked VHS tapes.

The difficulty these organizations encounter is how to properly deal with such physical material and turn it into organized, labeled, and safely preserved physical archival content, which could only be digitally archived.

Based on the substantial and consistent feedback we have received to that effect, we know this to be a common situation among CSOs—potential users of this manual. Thanks to the unique design of GIJTR’s project “Supporting CSOs in Digital Archiving,” this manual has the benefit of having been piloted by four CSOs and then reviewed by a wider group of relevant CSOs that provided their comments and recommendations.

Much of this feedback pointed to a need for detailed, hands-on instructions on properly approaching, handling, organizing, and ensuring long-term preservation of unstructured physical material the CSOs wish to archive before the digital archiving process can begin.

Additionally, the need for this type of practical guide came from another line of CSO-provided feedback, stressing that the manual should lay out in more detail and hands-on form the necessary archival procedures and concrete tasks CSOs need to take in organizing, describing, and preserving the physical material as a precondition to its digital archiving.

To the great benefit of this manual and its future users, precisely such a document that provides detailed guidance on organizing and archiving unstructured physical materials has been developed organically as part of the piloting of this manual's draft version. The National Coordination of Widows of Guatemala (CONAVIGUA) was one of those four organizations piloting the draft of this manual that faced the challenge of organizing and archiving their unstructured physical material before they could use the manual to create a digital archive. To address this, CONAVIGUA—with support and mentorship from GIJTR—engaged an external archivist to help them organize and archive their physical material. As a result of this process, they created a guide on organizing a physical archive in 10 steps.

Given that the document has been produced in such an organic manner as part of the project, we have included this guide in the manual in its original form as direct input from the field from the very CSO, who identified the need for it while implementing the draft manual. We, therefore, point the readers in need of hands-on, practical guidance for archiving and preserving their unorganized physical materials to this guide titled “How to Organize Physical Archives in 10 Steps,” developed by Marc Drouin with contributions from Daniel Barcsay and Ludwig Klee, in the Addendum II at the end of the manual.

Cleaning and Backup

Before working with the material intended for preservation, we must clean and back up the born-digital content.

We should clear the working space for our physical items and lay them out, box by box, to clean them sufficiently to be handled further. This should always be done wearing protective gloves. At this step, we might note and record any items that might be visibly damaged or degrading.

Anytime we work with digital items, we must perform an antivirus check to ensure the files are not infected or corrupted. This should always be done by connecting storage media containing the material to a safe computer, not connected to any computer networks. Finally, if you do not have a backup of your born-digital files, you should make one immediately before doing any work archiving them.

Material in digital form is exposed to various risks, from fire hazards through infection or corruption when used in an unsafe computer environment to malicious cyberattacks or simple human error. Therefore, making more than one copy of the digital material is fundamental to achieving a basic level of data security. Further, if our resources allow us to use different types of storage media for backup, we can lower the risks for our data. Best practices in managing the backup of digital archival material include:

- Having multiple independent copies of the digital material.

- Copies are geographically separated into different locations.

- The copies use different storage technologies.

- The copies using a combination of online and offline storage.

- Storage is actively monitored to ensure any issues are detected and corrected quickly.

At this point in the process, it would be sufficient for two backup copies to be created and stored on two separate storage media held in two locations, if possible.

Identification Inventory

Creating an overview is the first step in processing the material we wish to preserve. In essence, we need to map out what our material contains, in which format, how much material there is, and what state it is in. This should be done on the level of groups of items, not individual documents or objects. This process will create a table containing a list of item groups with key information about each.

The item groups first need to be identified. This is done based on existing information and documentation about the material. Typically, an organization will already have some overviews or lists of different parts of the material. Compiling information from such documents can be a good start, aided by institutional knowledge of the material and any other information we have. This should be complemented by a hands-on review of the material, both physical and digital, either by going through boxes and shelves or by a review of folders contained in digital storage units. In the process, we should note any additional or separate groups of items we identify. This will allow us to create the initial list of identified item groups, which we can then place on a table and call “Identification Inventory” or simply “Inventory.” In addition to listing the item groups, the Inventory must include information about the type, format, size, amount, condition, location, and storage space/media. An example is provided in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Part of an Inventory Table with rows listing the item groups and the columns containing the attributes on which the item groups are described |

|---|

These are the basic attributes of our item groups that we will need to know before proceeding further with the process of selection, organization, and describing the material. This is also necessary information for the development of the General Plan. A brief explanation of what should be considered in assessing item groups on each of these attributes is provided in Figure 4.

|

|---|

Figure 4. Description of attributes on which item groups are assessed in the Inventory Table

Selection and Prioritization

Once the Identification Inventory provides us with a clear overview of what source material we have, how much of it, and in which shapes and forms, we can proceed to decide which groups of materials should be preserved, for how long, and what the order of their preservation should be.

Here, it is important to stress that, given the nature of the material the CSOs documenting mass human rights violations are working with, organizations often wish to preserve everything, as all the material they have collected seems important and valuable. In some situations, this might indeed be the case. However, more often than not, preserving all the source material is neither necessary, reasonable, nor sustainable. For example, a careful assessment might uncover that some of the material is already preserved in another archive, the material does not hold any added value, it came from a compromised source, etc. Further, it could also be due, for example, to the amount or size of the source material or that long-term preservation of it all might be simply unsustainable, as preservation costs might be too high or organizational or technical capacities might not allow it.

Therefore, we need to conduct evaluation, selection, and prioritization of the source material for archiving and preservation. In archival terms, this process is often referred to as “appraisal.” The key step in this activity is development of a set of criteria to which we will evaluate the identified item groups and base our selection and prioritization decisions. These criteria should in turn rely on our Guiding Principles as well as on feasibility, sustainability, security, accessibility, and legal liability considerations.

Selection

Again, there is no universal set of archival criteria for selection and prioritization of source material for preservation. Different types of archives, source materials for preservation, and community and user contexts will affect which criteria are relevant to include as part of the selection process. Figure 5 offers a list of questions that can serve as the basis for devising a specific set of selection criteria tailored to a given archive’s characteristics and context.

Responses to the questions posed in the selection process should be recorded in a Selection Report and preserved for future reference, as decisions regarding the selection and preservation of archival objects will need to be reviewed in later stages and further iterations of the digital archiving cycle. Ideally, during the process, each item group would be listed and responses to the relevant selection questions written down. For the Selection Report, it is sufficient to note the key decisions made in the process and the reasoning they were based on. We might conclude that certain item groups contain subgroups of items that should be included in the archive, as well as others that should not. In that case, we should divide this item group and separate items that should be included from those to be rejected, creating two or more new item groups, as appropriate. These changes should then be reflected in the Identification Inventory.

As a result of the selection process, each item group should be marked as either “selected for inclusion” or “rejected,” in which case it can be removed from the Inventory and the rest of the source material. Alternatively, you might also introduce a category of item groups selected for “potential inclusion,” if appropriate. An additional column should then be created in the Identification Inventory and each item should be marked based on its assessment in the selection process.

Prioritization

The material selected for preservation cannot be processed and archived all at once due to resource, capacity, and technology limitations. Further, some segments of the material might require immediate preservation or digitization. Therefore, it is useful to assess and categorize the level of priority of different item groups for preservation and digitization. In this way, the material in most urgent need of preservation can be given priority. Further, this allows us to plan for any specific security, access-related, technological, or other arrangements that might be needed for the prioritized material.

The main considerations in decision-making on prioritization include:

a) current state of preservation (i.e., whether the material is damaged or in poor state or could easily be lost or destroyed)

b) whether there is an urgent need for availability of the specific material (e.g., for judicial or other transitional justice purposes, or in order to provide important information to the public or key stakeholders, etc.)

c) whether to give priority to the preservation of objects that have particular value for the archive, community ,or organization in line with the Guiding Principles

Specific considerations for prioritization will, however, always depend on the characteristics and context of any given archive, the purpose of the archive, and its goals, size, content, etc. Therefore, there might and should be other tailored criteria of prioritization developed for any given archive.

The outcome of the prioritization assessment should be the classification of each group of the material selected for preservation into priority classes (e.g., Priority levels 1, 2, and 3). Accordingly, an additional column should be added to the Identification Inventory wherein each item group will be marked in line with its assigned level of priority.

Organization and Description

Once we have an Inventory with basic information about the selected item groups for preservation, we can proceed to organize and describe the material. This is a necessary action to allow further archival processing and preservation, as well as to ensure that the future archive is structured, which will allow it to be manageable and searchable and ultimately that its content is accessible. This step has major importance in the process, as it will be the basis for the structure of our future digital archive, with repercussions on all aspects of its development.

Organization

Organization of material for digital preservation involves introducing a certain logical and hierarchical order into it and thereby devising its structure. This is done on the level of item groups identified through the Inventory, using an organization’s knowledge and understanding of the material.

The process of organization of the selected material entails the entire content of selected material being divided into several fundamental groups, each based on one or more common features shared by item groups they contain. These most-generic groups are then divided into smaller subgroups of material, and so on down to the level of individual items.

The most generic groups of material are often referred to as “collections,” or in strictly archival terms “fonds.” Each collection is divided into “series,” which can contain individual items as well as “subseries” and “folders” (sometimes also referred to as “files”), which are smaller, subordinated units of structure that then also contain individual items. See Figure 6.

Figure 6. Diagram showing an archive’s structure

This process of grouping, ordering, and devising the structure of the material—which, in archival terms, is referred to as “arrangement”—cannot be conducted by following a cookbook-like instruction manual. It requires analysis and consideration of the material and the context in which it was created, discovered, or received. The goal is to devise a structure and order that will preserve as much of the original context of the material as possible, including the information and meaning contained in the original relationships between groups of material. To achieve this, the archival rule of thumb is to arrange the material with respect to its “provenance” (i.e., origin or creator) and “original order.” This means mirroring, or following to the greatest extent possible, the structure and order that is already contained in the material itself. The presumption here is that there is either an obvious or underlying logic and order to the organization of any given group of material selected for archiving, and that in the process of organizing the source material we can identify or uncover this logic and then mirror it.

However, this approach is applicable only in cases where there is a clear or discernible order and structure to the material. This is often not the case for CSOs aiming to create digital archives of various material related to human rights violations. On the contrary, while some segments of the material CSOs are working with might be structured and ordered, there will usually be larger sections of it that are only partly or inconsistently structured, or that have no order to them at all.

In such cases, we should not attempt to preserve the “original chaos” found in the material. Rather, we should proceed to arrange it in a way that will best facilitate its use and management, while also relying on the analysis of the material itself. This can be done by devising several possible criteria for grouping of the material (e.g., based on its authorship, the function it served, the action it was a part of, or similar). These initial criteria can then be tested by applying them to a sample of the material. Based on the feedback from this piloting process, through which we will eventually identify the criteria that best suit the material at hand and allow for developing a distinctive structure of collections and series into which all item groups can be logically placed, we can tweak the test criteria further.

The result of this exercise will be an archival structure of collections, series, and, if appropriate, subseries and folders into which all identified item groups can be logically and meaningfully added. This archival structure can then be visually represented through a hierarchy tree or similar scheme.

To complete this stage, we need to revise our Identification Inventory and turn it into a table that reflects the newly developed archival structure so that its elements—collections, series, subseries, and folders—become the main unit of analysis. An example is provided in Figure 7. This table of archive’s structure will be a necessary tool for the next steps in archival processing of the source material, as well as for further development of the General Plan and completion of the Planning and Organizing stage. Figure 7. Table of archive’s structure with collections, series, and subseries as units of analysis

Description Now that we have organized our archival material, we need to describe its content in a way that will allow anyone to search for, locate, and access items in the collection. Description of archival material also enables its proper preservation and guides future users by providing important contextual information. It further enables establishing connections between items, even from different series. Simply put, without description, an archive would be more of a form of storage in which it would eventually become impossible to find or manage content.

The first decision an organization needs to make at this point is whether the archive will need—and whether it is even possible—to include a description of each individual item or instead just describe the content according to the level of item groups (i.e., folders or above). A basic level of description of the material on an item level, at a minimum by identifying each item with a unique identification number, is necessary for further processing. For born-digital material, this can be easily done using software (which will be discussed later), while for physical material, we need to go through each individual item manually and identify it. More detailed description of content on the item level is certainly preferable, as it allows for it to be more easily searched for and located, as well as because it provides more detail and context, which all significantly improve future preservation and access. However, this might not always be possible, despite those potential benefits being of essential concern for human rights archives.

The source material could contain an extremely large number of items, thus making it impossible to describe each one; or the organization could be unable to raise the needed funds and resources; or there could be a lack of time due to urgency to proceed quickly for safety or preservation reasons. Whatever the case, a decision should be made by carefully weighing the benefits on the one side (in terms of improved access and preservation) and the downsides on the other (including feasibility, time, and resources required).

The same trade-off applies to the second main decision we need to make at this stage, which is in how much detail and with how many elements do we want to describe our content, being mindful of our practical limitations. Including more elements of description will allow us to provide better access and more contextual guidance to users, but it will also require more time and resources. Again, each organization needs to select the elements of description based on the individual circumstances: size and characteristics of its archival material, type of access it needs to provide, and organizational capacities.

The elements of archival description, also known as “descriptors,” provide data on location in the archive's structure, physical and technical characteristics, informational content, and the function or purpose of archival item(s). There are different groups of such descriptors, the most relevant being general, content, and technical descriptors.

General descriptors record information that identifies and locates items, folders, subseries, or series within the archive, such as: ● A unique code or number ● Series/subseries/folder ● Title, author, date of creation

Content descriptors record information contained in an item, folder, subseries, or series regarding such categories as: ● Theme ● Location ● Time ● Actors

Technical descriptors record physical and technical characteristics of an item, folder, subseries, or series, such as: ● Storage location ● Storage media ● State of preservation ● Format, volume

There are also numerous other possible descriptors, some widely used, others specific for a given archive. Each archive will select those best tailored to the needs of its material, bearing in mind its Guiding Principles.

For CSO human rights archives, a particularly important set of descriptors is one recording private, sensitive, or confidential information present in the archival content. It is essential for a human rights archive to be aware of any such legally or otherwise protected material so that it can appropriately manage and control access to it.

Our task at this point is to analyze and review the content and its context in order to describe at the level of description we selected—items, folders, subseries, or series—in relation to each of the descriptors selected. We then record these descriptions in the table of the archive's structure we created in the previous step.

With this, we have completed the organizing phase of archival processing of our invaluable material for preservation. Now we must leave the safe haven of established and standardized archival procedures and depart into the restless seas of digital archiving, where ever-changing technologies are, for better or worse, inseparably intertwined with archival processes.

The first step on this journey is selection of the software and hardware framework of our future digital archive—the Digital Archiving System.

Digital Archiving System

A Digital Archiving System is a technological infrastructure of a digital archive. It defines the scope and limit of the archive’s functions and is instrumental in the archive achieving its primary aim and goals and upholding its General Principles. Therefore, selection of a Digital Archiving System has to be built into the planning stage of digital archive development as its essential element.

What Is a Digital Archiving System? The main goal of digital archiving is to ensure that the invaluable content we are preserving remains unchanged and accessible long into the future. This can be achieved by implementing an adequate and sustainable technological framework, or as the Digital Archiving System, for our digital archive.

A Digital Archiving System is a system of software and hardware components that consists of databases, software tools that manage databases, and storage media. A database stores information about the archive and its contents in an organized collection. Any table, such as the Inventory we created in the previous step, could be seen as a form of a rudimentary database containing information about an archive. An archival software tool then allows for management of a series of such databases, their content, and relationships between them. Archival software also serves as an interface between databases contained in the Digital Archiving System and the system’s users. The software enables us in practice, for example, to add item groups to our Inventory or create a new subseries.

The databases and software tools are merged together and make up the main software component of the system: a digital archiving software that allows us to manage an organized collection of information about the archival material.

The digital archival material itself, however, is located on storage media—typically physical devices that can store, retain, and make digital archival data available for retrieval. Well-known examples of storage media include a hard disk drive, flash memory, and DVDs. Until recently, digital content was stored only on individual pieces of different types of storage media, such as a single hard disk or CD. However, in the past two decades, two new forms of storage media have emerged: server-based storage systems and cloud-based storage.

A server-based storage system is usually located at the archive’s premises and comprises multiple storage media contained within a server that provides additional protection and allows for the recovery of data in case of a failure. Their set-up and management require advanced IT expertise.

Cloud-based storage is, in essence, outsourced server-based storage—a commercial service providing online storage and access to data. It is relevant to understand that when we store our data in a so-called “cloud,” it is in fact stored on a large-scale, server-based system of a company we hire for this service.

Functions of the Digital Archiving System

The software and hardware components of a Digital Archiving System work together to enable performance of the key functions of a digital archive, including storing, backing up, preserving, maintaining integrity and authenticity, safeguarding, providing access, managing, and eventually migrating archival data. In support, and to complement these main functions, a Digital Archiving System needs to enable us to perform a whole range of specific tasks and actions (e.g., checking data for errors, restoring lost data from backup, restricting access to sensitive data, and many others).

Given that a Digital Archiving System performs such an essential role, it is critical to select software and hardware solutions for it that will adequately provide for the specific needs of a given archive, which define the requirements it will have from a Digital Archiving System.

Such requirements are always specific for any given archive. In defining them, we should relate them to the General Principles of the archive: its purpose, aim, goals, and responsibilities. We also need to consider practical, logistical, and resource-related aspects of the Digital Archiving System we choose to implement, as well as our organization’s current and potential capacities to support it. Figure 8 lists some of the aspects of our archive that require consideration and analysis when selecting a Digital Archiving System.

Responding in writing to these and other points that might be relevant for a concrete archive will give us an overview of its specific needs. These can then be translated into our main requirements for a Digital Archiving System. In selecting components for our Digital Archiving System, we will seek solutions that, as much as possible, meet these requirements.

The process of selection of the Digital Archiving System software and hardware components should be recorded and documented in terms of analysis and reasoning on which it is based. Documenting the process facilitates any future modifications, upgrades, and eventual migration of data to new Digital Archiving Systems.

We provide example lists of main requirements for a digital archiving software and storage media for a CSO digital archive in the Addendum III. Again, each archive will need to include its own tailored lists of requirements. Moreover, these main requirements will need to be further devised and specified as the selection process progresses and concrete software and storage media solutions are being reviewed and considered.

Selecting Digital Archiving Software The archival software solutions come in different shapes and sizes and there is a wide range of options available. Different options provide for a different set of functions and vary in quality of performance. They also differ in terms of financial and human resources, technical expertise, and organizational capacities their purchase, implementation, maintenance, and development require. The key distinction is between commercial digital archiving solutions sold by software companies and open source software developed by communities of programmers that, importantly, is free to use. Both these options have their benefits and their disadvantages that need to be carefully considered before we make the selection. The list of requirements from the Digital Archiving System (see Addendum III) will provide useful guidance in this process, as the two different types of software solutions can be evaluated against it. The key distinction between open source and commercial digital archiving software is not whether one is free and the other is not; rather, they are grounded in differing methodologies, approaches, and sustainability models, which leads to them having advantages in some areas and disadvantages in others. In a nutshell, by selecting one type of software over the other, we select between prioritizing either flexibility or usability of our archive. Open source software is more flexible and allows for quicker and innovative changes to the structure, elements, and functions of the archive. At the same time, however, it requires more time, effort, and expertise to use, maintain, and develop than does a commercial solution. Another essential dilemma in this process is whether we will select a comprehensive, all-in-one solution or a modular solution, which is a combination of individual software tools working together in one system. The former provides all archival functions within one software solution and is usually more user friendly for management and use. The latter provides more opportunities to fine-tune the system’s functions and introduce new options or services. Once we have made the strategic decisions on whether we will implement an open source or commercial digital archiving software, and an all-in-one or a modular solution, we should select a concrete product among the many available. Our list of requirements will again serve to identify the products that provide the best possible fit for our digital archive in terms of functions, actions, and tasks it is required to perform while being feasible and sustainable in light of required resources. It is a good practice to test, on a sample of material, several software solutions that you are being considered in order to test their compatibility with our archive and get a better sense of their look and feel, functionality, and efficiency. It is not advisable to apply software solutions that have recently been developed and therefore not yet been widely applied and tested. Rather, we should opt for a proven and widely used solution and carefully analyze available information on its performance, evaluations, and user experiences. Reaching out and directly exchanging experiences with other CSOs that are considering or implementing such software solutions would be particularly beneficial. Selecting Storage and Backup Media Similar to the selection of digital archiving software, we should make a decision between the main types of archival storage media and their respective advantages and downsides. The most frequently used storage and backup media for archiving include external hard disks (e.g., HDD, RAID, SSD, or flash storage), optical disks (e.g., CD, CD-ROM, DVD or Blu-ray), magnetic tape, server-based storage systems, and online cloud storage. When selecting storage media, the solution might involve more than one type of a product, as such a strategy would improve data safety and backup. For example, if resources allow it, we could opt for HDD external hard disks as the main storage media and use online cloud storage as a backup. Different archives will have different priorities in setting the selection criteria. However, there is a set of dimensions that are almost universally considered relevant, including storage media longevity, capacity, viability, obsolesce, cost, and susceptibility. A useful overview of these criteria, along with other information relevant to the storage media selection process is provided in the UK National Archives publication “Selecting Storage Media for Long-Term Preservation.”

12:15